Is it because my work isn’t good enough to get traditionally published?

Yes. No. Maybe. I don’t know. (That’s a rude question!)

Traditional publishing is a temperamental creature. It’s not always about the quality of your work. It comes down to this question: Will the book sell? Publishers are in the forecasting business. They’re making an informed guess. Brandon Sanderson couldn’t get his work published for the longest time because publishers wanted him to be “more like George R.R. Martin.” And yet, Sanderson’s work is incredibly popular right now. The publishers are doing their best to forecast on trends, but who knows?

And even before you get a publisher, first, you need an agent. The agents are trying to figure out what the publishers want. So your work isn’t always being judged by its merit alone. Instead, it’s a forecast of a forecast. The agents and the publishers are hoping your work is malleable enough to twist and rework into something they think can be marketed and sold. It makes me wonder if The Hobbit or Lord of the Rings would have been published by today’s standards. (Tolkien is many things, but getting to the point within the first 10 pages is not his strongest attribute.)

However, this isn't about Tolkien or Sanderson, it's about me.

I tried to find an agent for Wear Chainmail to the Apocalypse. I spent about a year searching. I’m not gonna lie; it was rough. I had another author tell me, “The publishers aren’t accepting apocalyptic stories right now.” And she was 100% correct. (Coincidentally, a year later, COVID happened. The apocalypse is back, baby!) For my sanity, I decided to give up on traditional publishing and self-publish the novel. Lo and behold, people liked Wear Chainmail to the Apocalypse. It wasn’t a bestseller, but that’s not the point. It found an audience.

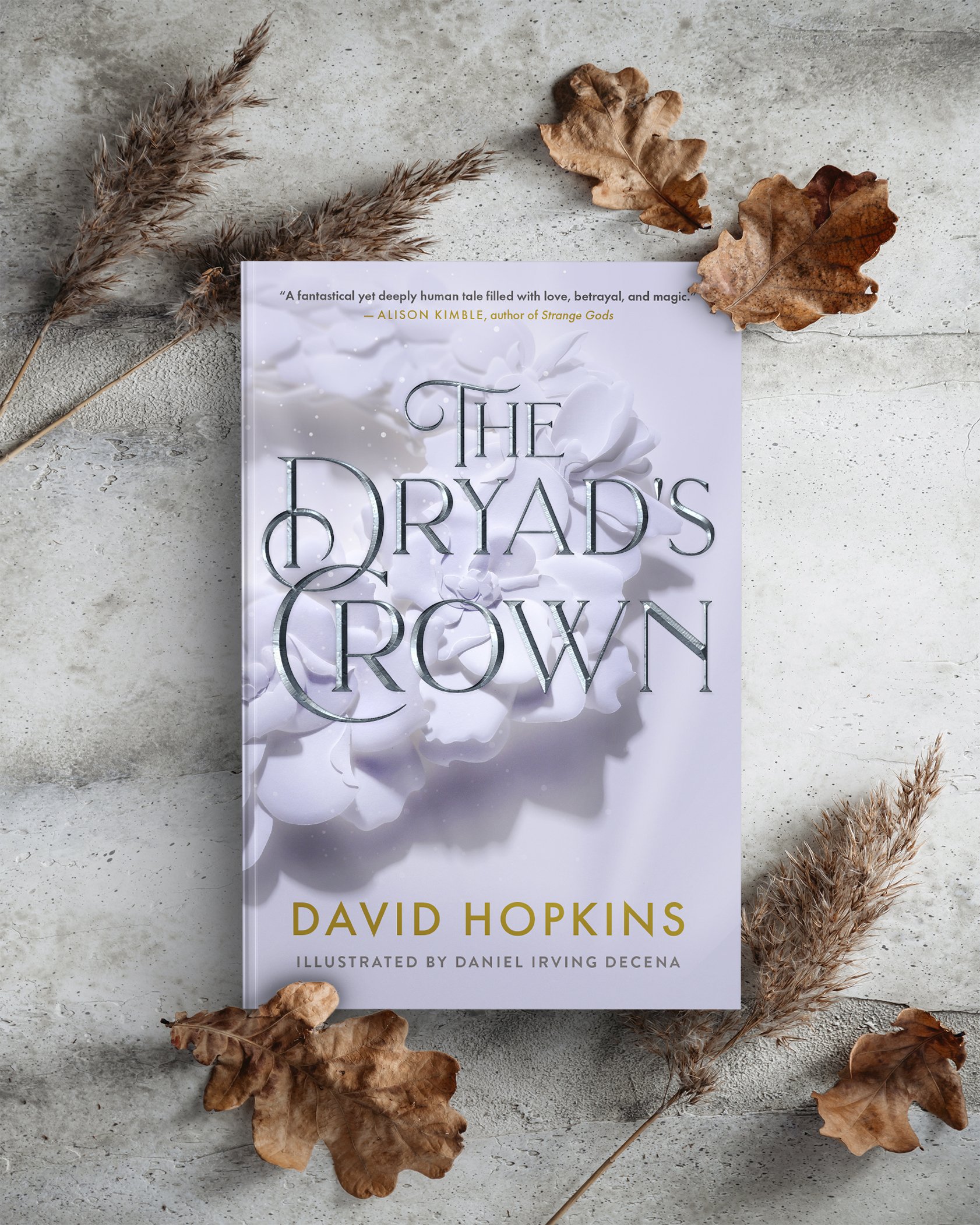

For The Dryad’s Crown series, traditional publishing wasn’t an option. I’m writing an epic fantasy set in an “open source” world. That means, while I own my story and my characters, I’m choosing to not own the setting itself. It’s available to anyone who wants to contribute to it. My assumption is that publishers wouldn’t want to buy something they couldn’t own. Thus, we’re self-publishing.

My hope is that The Dryad’s Crown finds its audience too—and over the course of the next few years, that this ten-book series will find a large enough audience to where self-publishing isn’t simply an option of last resort, but a preferrable path. With Patreon and other crowdsourcing platforms, becoming a full-time author is doable. I’ve done the math. Granted, it’s very basic math, but I’m not far off.

And if I can build a dedicated readership through my self-publishing—whenever I do decide to write something again for traditional publication, it will be a no-brainer for any agent. (“His independent work sells . . . how much?”) As a self-published author, I become delightfully dangerous because I can always walk away from a bad offer, knowing I have an alternative.

Why do I self-publish? Flexibility, a faster turnaround, freedom to choose my team (designers, illustrators, cartographers and editors), and the freedom to make outrageous creative choices.

You don’t read a self-published author to get more of the same.

Another reason is the simplicity of the exchange between author and audience. First, foremost, and always, I care about my reader. Yes, it would be nice to have an agent who spends their time thinking about how to best launch my career. It would be nice to get a multi-book deal from a company that has published some of my writing heroes. It would be nice to walk into a bookstore and point to my work—to have exposure with more reviewers, to set up more book signing events, and to be considered for more awards. These things are just not easily available to self-published authors. But as long as I am still serving my reader and giving them something they can enjoy, I’ve done my job. And that’s enough.

You can read and find out for yourself if it's any good.