The Lucky Buck Poetry Club

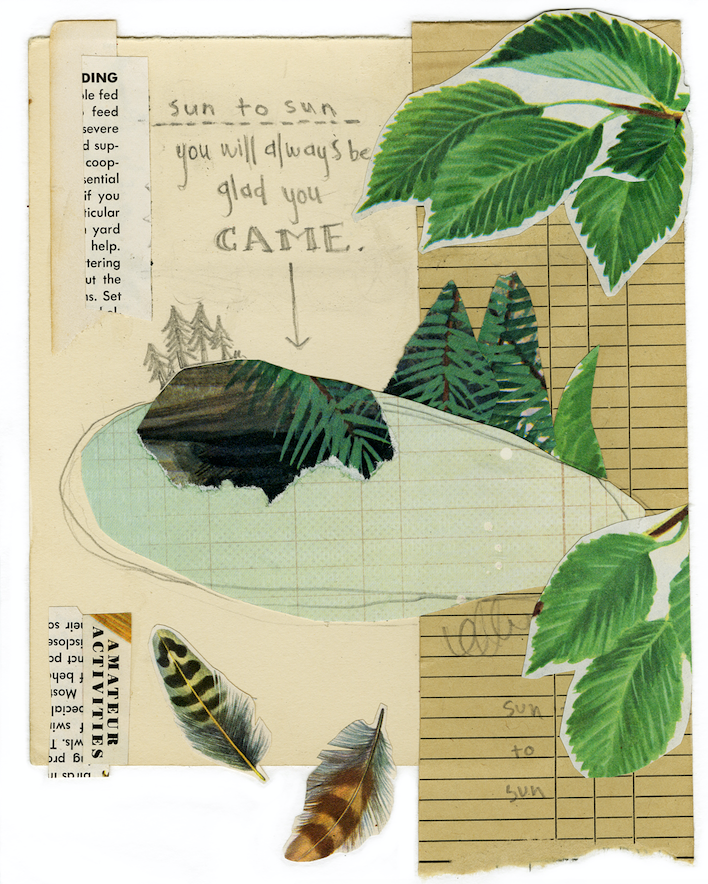

Collage by April Hopkins

When Charlie finished reading, the silence returned. No one knew how to react. Son of a bitch. Charlie wrote a poem.

By David Hopkins

Don was not disappointed; he was devastated. The roof of the bar, the Lucky Buck, caved in from the weight of last night’s snow. Don sat in his pickup truck, staring at the wreckage. The snow on the roof, which melted and re-froze into a heavier block of ice, exploited a weakness in the tired structure, broke through and everything gave way. The hole was massive. More snow drifted in.

Don kept his truck running, and stepped outside. The cold left him breathless. He gasped and zipped his coat to his chin. Don took a step towards the bar and then slipped on a patch of the icy sidewalk. The salt did little to melt anything. Don regained his balance and made it to the door. It was locked. There was a note posted inside the small window: BAR CLOSED. CAN YOU GUESS WHY? No doubt written by Sally who arrived earlier that morning. Don rested his head against the entrance. He could hear the creaking of the Pabst Blue Ribbon sign above him.

Don and his friends loved the Lucky Buck. They would meet almost every day after work, for every Packers game, for birthdays, for any special occasion, after his niece’s first communion. The Lucky Buck was the worst insulated building in town. The heater was always cranked full blast to fight a losing battle against the cold. Neon signs advertised Miller High Life and Milwaukee’s Best. These signs hung on the wood paneled interior. A large mirror behind the counter bore the name of Wisconsin brewer Jacob Leinenkugel. (Don and his wife Rheba toured the Leinenkugel brewery last summer. He bought t-shirts for Charlie, Nick, and Arnold. On the car ride home, Rheba was irritated at him for not buying her anything. She received Charlie’s shirt as consolation.) The Lucky Buck had a row of dashboard hula-dancers around the cash register. A Packers flag draped near the restroom doors. A magnificent 20-point buck, the centerpiece of the establishment, was mounted high on the far wall. The deer was named “Lucky,” of course. Don and the guys always claimed the table nearest Lucky whenever possible.

“Well. That’s a shame.”

Don lifted his head from the door and turned to see Arnold standing behind him. Arnold had walked from his house across the street.

“We could always go to Last Shot in Remington,” Don said.

“Nah,” replied Arnold. “Thirty miles away. It might as well be on the surface of the moon.”

Don and Arnold paused. The conversation wasn’t over. They just preferred these extended moments of reflection before continuing. Even if they were both freezing, they wouldn’t rush and show weakness.

“How about we get some beer at Pick ’n Save and go to your house?” Don pointed past Arnold to indicate the obvious. “It’s right there.”

“Yah. That’ll do.”

Don got into his truck. Arnold turned around and walked back.

Before they arrived, Arnold picked up around his living room. The place wasn’t clean, but no one could complain about it being messy. The house was his father’s. When Arnold and Kaye divorced, he moved in with his father. His father had cancer and died a month later. Arnold continued to live in the house, and didn’t have the desire to get rid of his father’s things. Arnold would not sleep in his father’s bedroom. He stayed in his old familiar room.

When Sally had returned to the bar, Arnold walked over to see if he could help. Sally didn’t have anything for him. He asked out of obligation, but didn’t want to stay. Arnold’s ex would be over soon to assess the damage. She was the bar’s insurance agent. Arnold preferred to not be there when she arrived. Before leaving, Arnold suggested he could keep Lucky safe at his house, so the weather wouldn’t damage this fine taxidermy. Sally let him borrow the deer.

Arnold was readjusting Lucky on the wall when he heard a knock at the door. It was Nick. He walked into the living room.

“Lucky looks good there, yah?” Nick admired the addition.

“I think so.”

“How did you get Sally to give it up?”

“Oh, I don’t think she minded too much. After all, there’s a hole in the roof of her bar. She has other problems.”

Nick held up his six-pack. “You want a beer?”

“Sure.”

Don and Charlie arrived soon after. Charlie lived the farthest from town. He worked on his father’s dairy farm and always looked half asleep by the time he arrived anywhere. It was something of a joke among the guys.

Nick shook his head as Charlie entered. “Are you sure you want to be here? You should go to bed.”

Charlie swatted at the air. “I’ll be fine. I just need to sit down.”

Charlie, Don, Arnold, and Nick sat in the living room, each with a beer in hand. They chose their seats to resemble the arrangement they had at the bar, with Lucky as their true north. Arnold’s accommodations fell short. The living room was too bright, too warm, and lacked the noises and creaks of the bar. They made several attempts at conversation, but nothing took. So, the quartet surrendered to silence. It wasn’t comfortable, but strained, fostered by the new environment. Nick was always the one to break any silence.

“So, the Lucky Buck.”

No one spoke. Nick continued.

“I told Sally she should’ve checked the roof. It’s an old building and when the snow comes, well, you know. Only a matter of time. She said insurance should cover the repairs, so there’s that.”

Arnold cringed, expecting someone to say something about his ex. No one spoke. Nick continued.

“Maybe when they fix the roof, she could get some more insulation in the bar, maybe a better front door. Everyone walking in and out, it’s no better than drinking out in the snow. It shouldn’t cost too much to get a better door. You can go to Home Depot in Wausau. They have everything. A new door and I betcha it would make a difference. The other day, I—”

“I wrote a poem.” Charlie interrupted as if Nick had not been talking at all. “You guys wanna hear it?”

The other three guys looked at Charlie as if he just confessed to murder. Where did this come from? Nick kept repeating his last word “I, I, I” until it diminished into nothing. Arnold took a sip from his beer, but kept his eyes locked on Charlie in case he had any other ideas.

“Sure, Charlie, read your poem,” Don said, encouraging and cautious.

Charlie reached into his pocket. Every sound inside and outside the house was magnified in the quiet moment. Somewhere, a truck drove over the crunchy snow. A dog barked in a nearby house. Charlie fished in his pocket until he withdrew a folded piece of paper. When he pulled it out, his pocket was inverted. Charlie did not bother to tuck his pocket back in.

“It’s called ‘Have You Ever Lived on an Island?’”

“Come see us on our island.

You will always be glad you came,

For you can leave your troubles

on the opposite shore,

And you will never be quite the same.

With Nature’s own voices,

all around us bring,

The geese that chatter

and land birds that sing;

All enjoying it so, from sun to sun,

So much to love, when the day is done.

Our house does sit,

on a high point to be,

Like a lighthouse,

on the edge of the sea.

We love to watch the fishermen have fun,

To see children catch, the biggest one.

It’s a wonderful island,

with water so blue,

All so quiet in a dream,

that did come true;

A part of God’s creation, for all to see,

A bit of heaven, for Betty and me.”

When Charlie finished reading, the silence returned. No one knew how to react. Son of a bitch. Charlie wrote a poem.

“Very nice,” Nick said.

“Can you read it again?” Arnold asked, and Charlie did.

Each of the men nodded their heads, taking in the poem, the bit of heaven that was Charlie’s island.

“Charlie, you don’t live on an island,” Arnold said.

“I’d like to. There’s a small island up north. I’d like to build a house on it.”

“Oh sure, but Charlie, you work on your dad’s dairy farm. How can you and Betty afford to build a house on an island?” Nick asked.

“Aw hell, it’s a poem,” Don said. “He’s allowed to build a house anywhere he wants in a poem. Right Charlie?”

“The lake could be a symbol or something.” Arnold added. “Charlie? Is it a symbol?”

“I guess so.” Charlie put the poem back into his pocket.

After a minute, the conversation shifted mercifully to football and the Packers. There was no game next Sunday, but they agreed to meet. They finished their beer and each returned home.

That Sunday, Nick arrived first once again with the other guys following. Like before, everyone sat in the same place. Then after the first beer, this time, Don spoke.

“Yah, so, I decided since Charlie wrote a poem I’d write one too.”

“Aw, hell, you?” Arnold grabbed for another beer.

“Hey now, if Charlie can write a poem, I think we all should have a chance.”

Don revealed a notepad from his coat pocket.

“I wrote this one about Rheba. She puts up with me and my crap. She never gets appreciated. I thought I should write something. But don’t tell her I wrote this poem. It’s not as good as Charlie’s—”

“Will you just read the darn poem?” Arnold said.

Don glared at Arnold. “I’m not going to read it if you’re going to be like that.”

The guys groaned. After some half-hearted pleading, Don relented and began to read.

“To my wife,

thank you for keeping our house clean.

To my wife,

thank you for never being mean.

To my love,

thank you for the dinner.

To my love,

I sure did pick a winner.

To my Rheba,

you worked so hard

to make our family happy.

To my Rheba,

I notice everything you do.

I love you.”

After Don read, he looked up for everyone’s approval. Nick waved his hands to indicate he had to read it a second time. The tradition was set. Poems must be read twice.

He did, then Nick offered his critique.

“I liked Charlie’s poem better.”

“See? I told you I shouldn’t have read.”

“Nah. It was okay. But the last part didn’t rhyme.”

Don looked over his poem, confused. “I rhymed ‘do’ and ‘you’ on the last line.” Don handed his notebook to Nick to review.

“Well, there you go.” Nick shrugged. “Still, Charlie’s poem was longer. Don’t you have anything else to say about your wife?”

“She took my t-shirt,” Charlie said. “You could mention that.”

“Are you still sore?” Don knew he messed up when he forgot to buy something for Rheba. She was taken for granted. He felt the poem covered this point.

“If you notice everything she does,” now Arnold was offering his opinion, “you could write a little more.”

“I’d like to see you write a better poem.”

“About your wife? Sure.”

The room broke into laughter. Arnold smiled and threw a beer to Don who failed to catch it.

The next time they met, Nick had a poem.

“This one is Snowy Night” He waited until he had everyone’s complete attention, and then he read.

“Whose woods these are I think I know.

His house is in the village though;

He will not see me stopping here

To watch his woods fill up with snow.

My little horse must think it queer

To stop without a farmhouse near

Between the woods and frozen lake

The darkest evening of the year.

He gives his harness bells a shake

To ask if there is some mistake.

The only other sound’s the sweep

Of easy wind and downy flake.

The woods are lovely, dark and deep.

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep.”

Nick was about to read his poem a second time, when Arnold interrupted him.

“How dumb do you think we are?”

“What—are you talking about?”

“You know darn well you didn’t write that poem.”

“Because I don’t own a horse? It’s a sym—“

“No, because you didn’t write it.”

“Are you saying I’m not good enough to write a poem like this?”

“Yah!” Arnold leaned forward to make his case. “I don’t know who wrote it, but that’s not you. When’s the last time you used the word ‘queer’ and meant something was strange?”

“Maybe I have talent you never knew about?”

“And maybe you’re full of shit?”

The guys have gotten into arguments before. They’ve argued about sports and politics. They’ve argued the merits of their favorite movies and who could win in a fight. They have spent a good hour arguing the finer points of which fishing lures to use. However, no argument has ever been as vehement as this one regarding the origin of “Snowy Night.” By the time they were too worn out with the endless circling of points and counterpoints, by the time the argument shifting into other contentious issues unrelated to authorship, a pile of beer cans covered the matted carpeting of Arnold’s house. They were drunk. Charlie left at some point, probably to bed. The other guys couldn’t remember. Finally, Don had a way to solve the debate.

“I know where my daughter’s English teacher lives. I bet he knows poetry!”

“He knows poetry!” an unbalanced Arnold echoed.

Each of them grabbed their coats and left the house. As they climbed into Don’s truck, Nick stopped.

“I need to go to the bathroom.” He walked over to the front porch steps and urinated on them.

Arnold laughed.

They drove through the quiet town. After two or three wrong turns, Don identified the correct house. The truck drove onto the front yard. Arnold and Nick, followed by Don, walked to the house. The lights were out in the neighborhood. Nick banged on the front door. Arnold urged him to knock softer. So Nick tapped on the door until a light turned on. A woman opened the door a crack. She was in a robe. She squinted at the earnest trio.

“What do you want? It’s one in the morning.”

“We need to speak with Mr. Teacher,” Don said.

“Really?” The woman was amused. “Hold on.”

Time passed. A man opened the door and stepped outside. He wore the same robe. He and his wife must have traded, as it was his turn to deal with these men. He was balding with wild hair and a full beard. “What do you want? It’s freaking cold outside.”

“You could help us with a discussion we’ve been having,” Arnold explained the situation. He tried his best to recite the parts of the poem he remembered. Mr. Teacher cut him off.

“Robert Frost. It’s one of the most well-known poems by one of the most well-known American poets. Did you really need my help? You could’ve googled it.” Mr. Teacher turned to leave. “You guys are idiots.”

He slammed the door and turned off the light. Arnold threw up on the welcome mat. After a fit of coughing, which triggered more vomiting, he wiped his mouth with a gloved hand.

“I knew you didn’t write that poem,” and more vomiting.

The Lucky Buck Poetry Club was born. They agreed to meet weekly. Each member brought his own beer. Each member had to share one poem he had written and one poem written by somebody else. Poems must be read twice, and the other guys were allowed to say whatever they wanted about the poem. The best compliment was always silence.

It was a secret society between the four of them. Nobody wanted anyone else in the town to know. The only person who had a suspicion was Teresa Wood, the town’s librarian. She was an east coast transplant to Wisconsin, an intellectual, long straight hair and a frame as narrow as a pine needle. Charlie and Nick would visit the library to find more poetry. Don borrowed his daughter’s literature textbook, and Arnold owned a copy of the Norton Anthology of Poetry. Arnold said it was his father’s. The wives never asked about the meetings. It gave the ladies a night off as well.

The poetry was about things they liked—beer, fishing, hunting, football, cars and trucks, their wives, their children, and the Lucky Buck. Charlie was the best poet. He could write about anything. He wrote about a snow blower once. The others swore the blower represented Charlie’s childhood, but Charlie never tried to interpret his work. Arnold found the best poems. He never shared any of his own. He would, but they weren’t real poems. Since the rules required him to read something that he wrote, he’d craft bad limericks on the spot.

“There once was a man from Sheboygen. Blah. Blah. Blah. Go to Hell.” This one was the kindest among them.

One week Arnold brought poetry by Walt Whitman.

“that you are here—that life exists and identity, that the

powerful play goes on, and you may contribute a verse”

This earned the longest silence. A beautiful silence, the men contemplated their own verse. “I like this guy, Whitman,” Nick said.

Everyone agreed.

“It’s not poetry though,” Don suggested.

“Are you kidding me?” Nick immediately defended his new friend Walt Whitman.

“Hear me out. I like the guy, but it doesn’t rhyme. It sounds like talking. Not talk-talking, but you know—”

“Like preaching, an oration,” Charlie said.

“Exactly! He’s preaching.” Don looked at Charlie. Since when did he throw around words like “oration”?

“It’s called free verse poetry, you goof.” Arnold sided with Nick.

“Oh sure. Free verse sounds like an excuse for when you can’t make the poem work like it should.”

“You don’t think Whitman could make something rhyme?” Arnold was getting angry. “He could rhyme circles around you if he wanted.”

After another half hour, they agreed to disagree. Walt Whitman was poetry to some and not poetry to others. Walt Whitman was good, and he was welcome at the Lucky Buck Poetry Club whenever.

In contrast, Emily Dickinson was universally disdained and outlawed from the group. Her poems were too short, and no one had any clue what she was talking about. Nick complained to Teresa Wood about Emily Dickinson who Teresa had recommended. Teresa mentioned this young poet was never published during her lifetime. Nick shared this information with the guys, and none were surprised.

Even though the club was kept from their wives and the rest of the community, people noticed something was different. One morning, Charlie’s father found him in a corner of the barn with a small notepad in his lap, staring off like an idiot. Charlie’s father snapped his fingers. Charlie jumped to his feet, shoving the notepad into his pocket. He then went about checking the cows. Nick was quieter. Usually, when he made his rounds delivering mail, he would talk to anybody on his path. Nick had become introverted and distracted. Don was the opposite. At dinner, Don rarely said more than a few words; now everything fascinated him. He listened to his children talk about their day, and Don would ask follow up questions. He would laugh, entertained by the slightest bit of irony. Arnold was always irritable, even more so after the divorce and his father’s death. In the past few weeks, that irritability transformed into an overwhelming exhaustion with everything —defeated, as if words had a weight and all the words were crushing him. He couldn’t hear someone speak without grimacing. Before he was unpleasant, now he was antisocial. He mumbled to himself and went for walks in the snow.

Don thought of Packers poetry night. The other guys loved the idea. In honor of Green Bay making the playoffs again, they composed odes to their team. There were poems about Aaron Rodgers and Clay Matthews, poems about Vince Lombardi and Bart Starr, the Ice Bowl and last year’s Superbowl win against the Steelers. Arnold, who still refused to write a legitimate poem, did put together a hateful free verse slam about Brett Favre. In a rare show of mirth, Arnold wore his foam cheese-head hat while reciting the poem. The other guys laughed and laughed, and Arnold tried to keep a straight face. On the last line, they all raised their beers in triumph.

Nick looked around the room, to see his friends in the ease of each other’s company, drinking beer and reading goofy poems. Nick realized it was possibly the happiest moment of his life. He was content. Satisfied. With this realization, he almost cried—not tears of joy, but from an understanding that he hadn’t truly been present in the other great moments of his life. His wedding and the birth of his son, he missed it all. He was there, but not attentive to the details, to the life around him. Damn Walt Whitman and Robert Frost, damn Langston Hughes, William Yeats, T.S. Eliot, Margaret Atwood, Robert Browning, Dylan Thomas, Ezra Pound, E.E. Cummings, Sylvia Plath, George Byron, and William Blake, and whoever wrote the Psalms, and that guy Pablo Neruda. Damn him too. Damn Charlie, Nick, and Arnold. Even damn Emily Dickinson, because although they banned her from the club, Nick spent an entire afternoon at the library trying to figure her out. Damn them all, because they noticed things and shoved it in his face. They made him realize he had been missing out, and his life was fleeting.

He promised himself he would change.

Arnold put the poem down and took a bow.

A few days later, the roof of the Lucky Buck was fully repaired. The bar re-opened, and life returned to normal. The poetry club dissolved, as none of them would dare share a poem in public and they missed their bar. Occasionally, they would talk in code with each other about some “good stuff” they found. Or they might pass notes to each other, new poems they were writing. They still visited the library. Teresa would reserve anything she thought the guys might like.

Don walked in an hour before the library closed. He was looking for Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. The library had three copies, but none were on the shelf. Don walked to the front desk.

“Your friends checked out all our copies.”

“All of them?”

“Charlie’s copy is overdue. You could always get it from him, and bring it back. I’ll then check it out to you.” She smiled. “Was it for your book club?”

“It’s not a book club.”

“I can see if the Marshfield Library has a copy they can transfer.”

“Don’t worry about it.”

Teresa tilted her head in silent apology. Don went back to the poetry section to look for something else to read on his lunch breaks.

On January 15th, the day of the NFC divisional round between the Green Bay Packers and the New York Giants, the guys all met at the bar to watch the game. Arnold reluctantly returned the buck to his place on the wall. They bought their beers and sat ready for the kickoff. Someone entered the bar and a gust of cold air followed inside. Don frowned then averted his glance. Arnold turned to see who arrived.

Kaye, Arnold’s ex-wife, stomped her feet on the mat to get the snow off. She came to the bar with some insurance paperwork under her arm. Kaye flinched at the sight of Arnold. She shouldn’t be surprised, but she was. They had carved territory in this small town, lines drawn to chart boundaries and avoid interference with the other’s life.

“Ah geez, I’m sorry. I can come back later.”

“No. It’s all right,” Arnold said.

Kaye walked to counter. She showed Sally the sections to be completed. Arnold looked at his beer, ignoring the start of the game. Then Kaye walked toward the door.

“Wait,” Arnold said.

Kaye stopped. Arnold pulled out a well-folded, well-worn piece of paper. He was shaking, and he had to pause at intervals to breathe.

“I wrote something for you. I’ve kept it with me, in case I saw you.”

“Arnold, I don’t think—”

Arnold then spoke to the other guys. “I wrote this the same night, right after Charlie shared his poem about the island.” He handed the paper to Kaye.

“It’s called ‘I’m sorry.’ So…” He began to recite it from memory.

“The snow has melted,

and the snow has refrozen.

Harder, heavier, testing the weak places, the vulnerabilities.

You left in the Fall,

and it’s only gotten colder.

I hope in the Spring I can mend,

but I’ve only gotten older.

The snow has melted,

and the snow keeps falling.

My words are harder, heavier,

testing my weak places.

I miss the wisdom of my father,

his life and wit.

How many second chances

does one fool get?

The snow has…”

He stopped. He couldn’t go any further without losing his composure. “You get the idea. The rest is there. You can read it.”

He expected her to leave and read it in the car or when she got home. But instead, she read the rest of the poem silently in front of everyone. Kaye, at a certain word, she broke. The tears started. She bit her lip to hold something back, and looked at him with a fierce tearful glare. She nodded her head once as a way to say thank you.

And then she left.